Today I want to look at The Wheel of Fortune and The World Cards for what they can tell us about the relationship between the temporal and the eternal. The Wheel of Fortune Card speaks to the changeable nature of all things while the World speaks to the background against which they change. By looking at the two cards together, we see how time and eternity, change and stasis and the world of the “deathless Gods” and that of mortals both imply and sustain one another. I hope to shed light on two philosophical prejudices that have, and most likely, will continue to bedevil the mind that tries to understand the “true nature” of reality.

The first is that the world, being nothing but change, can have no ultimate coherence or meaning. The most extreme iteration of this position is found in nihilism which holds that, because the world is (or seems to be) without an objective coordinate system, all moral or even practical action is rendered meaningless. Notice that there is a difference between claiming that the universe is without MEANING and that it is without STRUCTURE. One needn’t deny the existence of objective facts to be a nihilist (although some do), only that these facts have any meaning beyond themselves. For example, the FACT that a certain chemical is toxic to a certain insect doesn’t MEAN that I should become a conservationist or an exterminator. To derive meaning from the fact involves other considerations, the ecological implications of using the chemical or potential threat to health or property in letting the insect thrive. Of course, any of these facts are equally vulnerable to the question “who cares?”.

For most of human history the “who” in this question would have been answered with the name of a God or Gods or perhaps some more or less vague notion of the “common good”. But even if such answers satisfy some people, the fact that they might not satisfy all, demonstrates the fragility of meaning. You have to both believe in and, more importantly, care about the opinion of the Gods, or at least your fellow humans in order for appeals to these to found meaning.

Which brings us to the second prejudice, that the world MUST have one, and only one meaning. This prejudice arises from care itself. If we care about something; a cause, a person or people, the regard of a God or Gods, these become the source of meaning for us. It is easier to believe we love something because it is good than to believe it is good because we love it. If the former is true, we know that our sense of meaning is justified by something beyond ourselves, if the latter, meaning is rooted in the contingent nature of our affections. Since these are mutable and do not necessarily align with the affections of others who seem as committed to their idea of good as we to ours, our sense of meaning is always threatened by that of our neighbors. This is, of course, the source of all partisan conflict. Here, rather than becoming nihilists, we become “true believers” in one dogma or another about how the world “really is”.

These two positions; the nihilism of a world of constant change and the dogmatism of a world of fixed standards for everything paradoxically imply one another. The nihilist makes a dogma of the impossibility of meaning. Such a person may find it difficult to make even the most rudimentary commitments knowing that there is no ultimate reason for making any. The dogmatist, by contrast, always seems to feel the need to resist and suppress heretical ideas about the meaning and purpose of existence for fear that one of these ideas might prevail, leading the whole world astray. One might wonder, if there was, in fact, one and only one true source of meaning in life, why would any other appear attractive or even viable. In most cases, the true believer will site some corrupting influence who’s only purpose is to lead people away from the truth. But if there is only one true way, the antagonist must be part of that way. This is a position that can be supported by “scriptural evidence” from many traditions but, for many believers, the idea that there might be a reason for what ever they consider “evil” is a kind of third rail which must be avoided.

Some people will go to one extreme of this dichotomy or the other but most will move back and forth between them, being more nihilistic in some areas of life, more dogmatic in others. Nor do I necessarily believe that anything can or even should be done to correct the matter. What does interest me is the source of the conflict. I believe it rests in two equally potent intuitions which most of us have about reality.

First there is the sense of constancy that we experience as ourselves. When I wake, I feel myself to be the same person I was when I went to sleep. My name, location, relationships, plans, aspirations, fears, loves, hates – in a word, my IDENTITY seems a stable thing. When I put my feet on the floor, I expect it to be as it was the night before, that the things I touch and use each day will be more or less in their proper place and render the same services as they had before. All of this contributes to the sense of continuity which I extrapolate to the entire universe. Depending on how satisfied I am with the regular course of my life, I will experience this apparent continuity as a comfort or a curse, but in any case, I count on it to guide me in my actions.

Equally powerful is the sense we have that nothing lasts. Anyone who has lived to a certain age will know the sense of disorientation that comes from waking up one day and realizing that neither the world or even our bodies are as they once were. Our priorities and allegiances change, our physical and mental powers may fade, we may find the world for which we prepared ourselves in youth is not the world we find ourselves in today. It takes time to notice change but when we do, we may come to think that our earlier sense of continuity was merely a naïve take on the world or, we might suspect that our initial intuition was correct and the world has somehow become corrupted over time.

The well-known expression “the only constant thing is change” seems truer than the claim that the world is ONLY change or ONLY constancy. But if this saying is true, HOW is it so? It is here that The Wheel and The World provide clarification.

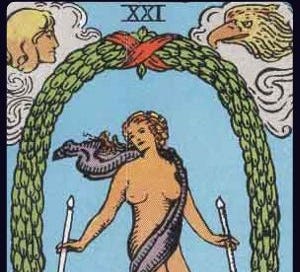

The first thing we should notice is that both cards have, in their corners, the four cherubic beasts: The Bull, The Lion, The Eagle and the Man (or angel). These represent the fixed signs of the Zodiac: Taurus, Leo, Scorpio and Aquarius respectively. The World Card relates to Saturn (Chronos) while The Wheel relates to Jupiter (Zuse). In classical astrology, Saturn is the outermost of the “wandering stars” and defines the boundary between the changeable world of the visible planets which move in their orbits and the “fixed stars” which form the background against which this movement occurs.

As “King” of the planets, Jupiter is the maker of law, but without Saturn, no law would be possible. Law requires a distinction between what is, and is not, permitted. But without Saturn, who establishes all forms of limitation and duality, there could be no distinction between is and is not, let alone permitted or not.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the fixed (or solid) constellations correspond to the height of each of the four seasons. But our sense of their fixity arises from the fact that we return to them the same time each year. They have not moved, we have. This is the reason why the heavens have always represented the eternal and unchanging while The Earth represents the changeable. The wreath on The World card represents the boundary between the changeable world and the unchanging realm of the Zodiac which is the world of the Gods.

The Wheel (of Fortune) shows us the world of change. That it retains the four beasts that are the fixed signs of the zodiac suggests that it is this backdrop against which change takes place. Imagine the kind of wheel one sees in a fair ground, the sort of wheel one spins to win some small bauble. A spring loaded “flipper” both acts to slow the wheel’s turning and indicate the number where the wheel “stops”. If it weren’t for this fixed point, the question of WHERE the wheel stops would have no meaning. A fixed framework outside of the wheel AGAINST WHICH the wheel turns define its’ turning. Change (the wheel) always takes place against a background of (at least relative) stasis.

The World Card (and Saturn) represents the difference between the zone in which change occurs and that which is ostensibly static. We might be tempted to think that this apparent stasis is illusory, but to do so, we must have in mind some idea or IDEAL of stasis. The Wheel of Fortune (and Jupiter) remind us that any idea we have of fixity is merely a gamble. We can “take a stand”, choose a number that we hope the wheel will settle upon, but we can never be certain that our number will come up. Nevertheless, if we do not take a number we are simply not in play.

Both the dogmatist who believes in some ultimate framework against which all things turn and the nihilist who deny such a framework are taking a number and playing a game – the same game we all must play. There is simply no way to avoid making a stand, choosing a number and hoping to win the Kewpie Doll. Life is, in this sense, a game but one we are compelled to play. We might deny or resent this but the Gods are Barkers and bid us “STEP RIGHT UP! STEP RIGHT UP!”.

I love this examination of the nihilist and dogmatist as polarities. I see them both alive in me at different times.